The vanishing nuns of Delaware County

Published in Religious News

PHILADELPHIA -- It was afternoon at the convent, and that meant bingo.

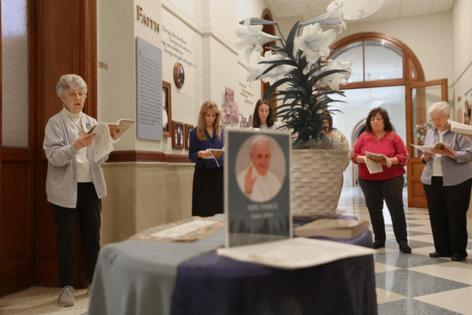

A dozen elderly women, some in wheelchairs, others with their walkers pushed aside, studied the triplets of cards in front of them. A life-size cardboard cutout of Pope Francis, newly deceased, waved beneficently down at them.

“Call the right numbers!” joked Sister Geralda Meskill, who is 97.

In its 170-year history, the Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia has survived the Civil War, the 1918 flu, the Great Depression, both World Wars, dramatic cultural shifts in how Americans relate to almost every aspect of daily life, including the Catholic Church, and now, 12 popes.

But it’s an open question how much longer the Sisters will survive. The Aston congregation is facing the same fundamental challenge as its peers across the country: not many women are signing up to take perpetual vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience these days.

“It doesn’t look hopeful at this moment,” said Sister Dolores Duffy, who is 91, about the future of the congregation. “But what is it? ’Hope springs eternal in the human breast: Man never is, but always to be blest.’”

The average age of the Sisters of St. Francis is 84; only two women have joined permanently in the last decade. When the youngest sister by more than two decades professed her final vows last summer at age 35, the congregation issued a press release: “Young Woman Joins Franciscan Order.”

In 2024, there were roughly 35,000 nuns in the United States, an 80% decrease from 1965, when there were about 175,000, according to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, or CARA, at Georgetown University. (There is also a nationwide priest shortage.)

Longer lifespans and high healthcare costs, plus fewer new sisters entering religious life, has meant congregations across the country are struggling financially, said Father Thomas Gaunt, CARA’s executive director. The Sisters of St. Francis are funded in part by a foundation that accepts donations, as well as the Social Security and Medicare benefits of the sisters. The women pool money and share resources.

And their work continues. On a recent Tuesday, some gathered in the morning to bless the wildflower and blackberry seedlings for Earth Day at Red Hill Farm, a six-acre farm the congregation owns across the street from the convent. Then they gathered for a morning prayer.

“You also told us you are the light of the world,” the sisters read. "You set our purpose to shine through our actions."

‘A prayer powerhouse’

There are 270 Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia, about 30 of whom live in the castle-like motherhouse, called Our Lady of Angels Convent, on a sprawling green campus in Aston.

Neumann University, the Catholic university the Sisters founded in 1965, owns that building now and rents office space and housing to the sisters. Other sisters live around the city and the country, in houses rented by the congregation.

Roughly 80 sisters live across the street in Assisi House, the retirement convent and home of the bingo game.

Though they are technically retired, the sisters at Assisi House are considered to be in “prayer ministry”: they write to prisoners, make food to be distributed in Kensington, and fulfill prayer requests. (“They’re really like a prayer powerhouse over there,” said Colleen Collins, director of companions for the congregation.)

Elsewhere, the Sisters of St. Francis teach ESL classes, distribute hot meals, work as doctors and nurses, and advocate for clean air and water alongside environmental groups. A new documentary, "No Risk, No Gain: The Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia," tells their story.

Some worry that their declining numbers and decreased visibility mean that future generations won’t even consider the convent. Many of the sisters who are now in their 80s and 90s joined St. Francis when they were 18 and 19, inspired by family members or Catholic school teachers who were already in religious life.

That’s how Sister Kathleen McCabe, who is 81, heard the call. Growing up in Roxborough and attending John W. Hallahan Catholic Girls’ High School, McCabe had always planned on becoming a nurse. But her religion teacher urged her to consider a nun’s life.

“As a very obedient young person, I went home and I thought about it,” McCabe said. “I went back on Monday ... I burst into tears, and said, ‘I think I’m supposed to be a nun!’”

After a period of “discernment” — how the Franciscans describe a process of figuring out what God intends — McCabe joined a semicloistered community that was drastically different from the one in which she lives today. In 1962, she became a nun alongside more than 60 other young women, part of the broader post-World War II baby boom that also filled convents.

At the time, the Sisters of St. Francis wore full habits and followed a highly structured schedule that determined when they ate, prayed, and went outside. Internalizing the maxim “idle hands are the devil’s workshop,” they scrubbed the convent in their free time until it sparkled, McCabe said, laughing.

That was just before the community underwent a series of radical changes inspired by Vatican II, the modernizing effort that remade the Catholic Church in the mid-’60s.

Today, most of the sisters wear ordinary clothes, not habits, and life at the convent is far more informal: There is Mass three times a week, some shared meals in the dining room, and prayer and discussion of faith in the evenings.

Researchers at Georgetown calculated that the 100,000 nuns who ran Catholic schools nationwide in the 1950s and 1960s provided work worth the equivalent of $3 billion each year, for free, to their communities.

Today, there are only a few thousand nuns involved in Catholic schools across the country, Gaunt said. As nuns die, the enormous amount of labor they provided for schools, hospitals, and the poor and marginal in every city has also diminished. It’s not clear who will replace them.

But many of the sisters of St. Francis are nonetheless at peace. The life of the Catholic Church is measured in centuries, they said, and what comes next is not up to them.

As Sister McCabe said: “God isn’t finished with us.”

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. Visit at inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments